If there’s one word I can think of to describe the first 400km of Uzbekistan it’s —

Roomy

Enough room to swing a cat. Enough room to swing several cats tied together, which is fine out here, there’s probably no RSPCA.

The first few days of Uzbekistan pretty much consisted of biking as far as you can on a road that ranges from average to poor. Stop. Turn left. Cycle away from the road for about 1km. Camp. Nothing interesting to report here.

When we did finally hit civilisation, it came in the form of Kungrad. The word civilisation’s pushing it though, the entire place was filled with rabble and chaos, and after being so long away from anything it only served to irritate me, so the prospect of finding a cheap hotel to wash away a weeks worth of dirt quickly turned into – grab some supplies and get out. In typical Uzbek weirdness we managed to find a shop that sold sausages, Coca Cola, and orange juice. Just those things, in huge quantities.

I had to wait till Nukus for a warm shower, there was a sign telling me to be conservative with the water, this is the desert after all. I ignored it. At this point we also needed to delve into the black market. We needed to change some of our US dollars for Uzbek Som, and our plan of attack was to aimlessly wander the bazaar.

As you go into Uzbekistan you have to declare what money you have. We brought a load of US dollars rather than trying to get any Uzbek Som beforehand, as we’d heard stories of people with bar bags full to the brim with fat stacks of cash. You’d think you just pop to the bank and change your dollars. Now that would be easy. The banks apparently give you a shit rate, about half of what you can get on the black market, so off we went.

It took about ten minutes, then a spindly bloke brushed past us muttering —

‘Exchange Dollar’

We agreed a rate, hustled up near an alleyway and swapped one crisp, hundred dollar bill for a black carrier bag full of dog-eared Uzbek Som.

‘Count this.’ Fredrik handed me a stack.

I’m shit at counting things. I last about a half a minute before I start thinking about something irrelevant, and it wasn’t long before I started giggling at the ludicrous nature of the situation – here were two European lads in a town which hardly sees tourists, in the busy part of town trying to count a carrier bag full of money. Luckily Fredrik isn’t so useless and after counting the lion’s share we decided it was pretty much all there, so we stuffed our pockets full and walked off feeling rich.

Until half an hour later when I went to a shop and was relieved of an entire handful.

Closer to the south near the Turkmenistan border, thanks to there being a river nearby, the Uzbeks start to make the most of all the land they have. Every inch is taken up with agriculture, which makes camping a bit more difficult, but at least there’s more to look at than pure, flat desert.

On the way down to Khiva we met another British cyclist called Clive. Nice bloke, but as soon as he mentioned his name all I could think of was the Monkey Dust sketch.

‘Where have you been Clive?’

‘I’ve been cycling through Central Asia across acres of barren desert.’

‘Where have you really been Clive?’

‘…’

Clive described the Uzbeks as ‘a little bit too ‘in your face”, and I know what he means, they’re a lovely bunch, but they get a little too intense sometimes. Fredrik picked up on this and asked why the British are so cynical, I think my answer was – ‘I dunno’, but I think it’s because we’re so ruddy great at everything.

We spent a couple of days in Khiva, an old slave trading post with a huge, mostly original, walled old town. It was a nice place, whilst being quite touristy, but nowhere near the levels of Bukhara and Samarkand, which I’d come to find out. It wasn’t devoid of Uzbek weirdness though, which we found out when we walked past a bloke taking a shit in broad daylight opposite the city wall.

At the time, when we left Khiva in the pissing down rain, I didn’t realise that it was the call for the end of summer. It was fun while it lasted. The next two nights of camping started getting cold. The second in particular was the worst on the trip. We’d managed to pitch up before the rain, we knew it was coming, what I didn’t expect was the wind, and I hate wind.

Camping on wet sand means your pegs are about as effective as a spoon in a bowl of porridge, so obviously halfway through the night I woke to find my tent doors flapping in the wind and rain, exposing my shoes which were soaked in a wet, sandy paste. I tried re-pegging my doors, but every ten minutes the wind tugged them out again from the churned ground like naughty child.

It was at this point I found out when the worst possible moment to get the shits is. There was no avoiding it, if I carried on with tent duty there would’ve been an even bigger problem. If you’ve never had to squat and squirt in a desert plain whilst being pelted by wind and rain, watching your tent try it’s best to roll away, then count yourself lucky.

I gave up in the end. I just laid in a tent which flapped about until morning, when some military blokes came over in a 4×4 and told us to leave. Gladly mate, gladly.

I felt pretty shit for the last couple of days to Bukhara. Maybe it was some dodgy food, which wouldn’t surprise me given the state of some tea houses, or maybe it was the cold, who knows. Tea houses in Western Uzbekistan turn into some miracle oasis, normally signalled by a radio mast on the horizon. Cycling through hours of desert with nothing to break the monotany, especially in the wind and rain, means you take any opportunity for some chai. I’m not sure if half of the places were actually tea houses to be honest or just a house, and as you enter some you’re not quite sure whether you just wandered into a crack den, but either way, you get some tea at the end of the day, and they get some money. Everybody’s happy.

After a town called Gazli, we bumped into the first, and probably only Uzbek cycle tourer; Ismael.

Ismael quickly established himself as balls mental by cycling on the wrong side of the road, swearing at oncoming traffic, but as he came closer that wasn’t the only thing that was mental about him. Ismael’s bike and ‘luggage’ was special. He had a pack of tabs selotaped to his front tube, a toothbrush in a Colgate box (considering Uzbek’s dental health this is probably the most mental thing), a paper cup acting as a bottle holder on his seatstay, and among other things, an entire melon taped to high heaven on his crossbar. There was so much selotape holding things to his push-rod that if you unwrapped it all the bike itself would probably fall to bits.

After cycling with Ismael for longer than we’d have liked he almost aggressively gave us half a huge sausage, a bit of coke, some bread, a tin of sardines and 1000 Som each. We tried really hard to refuse everything, but this pissed him off, such was Ismael’s weirdness and the Uzbek’s hospitality.

Ismael was cycling to Tashkent, roughly 800km away, I wonder if he made it. Probably not, when he left he biked off in the wrong direction. The plonker.

Bukhara brought the end of the line for Fredrik. Two months cycling together, from Istanbul to Uzbekistan, he’d had enough and decided to fly back to Sweden. A fine compadre. So, for about half a day, I thought I was going to go it alone, on my tod, the first time since Greece. Until I met Flo, a German cyclist who was heading in a similar direction. This tour, for him, was a loop down from Bishkek towards the Fergana valley, into Uzbekistan, heading through Bukhara and Samarkand before ending up Tashkent, except his rim had split along the way, leaving him to build a new wheel in Uzbekistan. No mean feat.

You learn something from everyone you cycle with. Everyone has different ways of covering the ground, camping, cooking, everything. Of course, no single way is correct, and what works for one person might not work for another.

I learnt a lot from riding with Flo.

Flo was a bit of a cycling veteran, he’d ridden from Germany down to Africa in a not too dissimilar fashion to me (‘quit everything, hit the road’), as well as tours in the UK, Scandinavia and then some.

We spent the best part of a week meandering towards Tashkent, with a couple of days in Samarkand, Flo’s major point of interest. The day after Samarkand was my first real meltdown of the tour.

I’ll rewind a little bit. I was sat in the courtyard of our hostel in the afternoon when I met Mr Yiu, a tiny old Japanese fellow.

‘Do you want to go and drink beer?’

‘Maybe in a few hours, it’s a bit early’ I replied in a uncharacteristic waft of common sense (don’t worry, it didn’t last for long).

‘Come on. I have to use all of this money!’ Mr Yiu replied with fistfuls of cash. He was right, Uzbek Som is about as useful as bumwad in Uzbekistan, never mind when you leave the place.

So in a few hours, Mr Yiu, Flo, Hugh and Emily (a Kiwi couple who had hitched from London) and myself went to a little Uzbek restaurant. Mr Yiu proceeded to fill the entire table with any meal they could muster up, whilst ordering as much beer and vodka as we could stomach, which it turns out, is a lot. The restaurant owner must have been rubbing his hands together, this must’ve been like Christmas for him, and he doesn’t even have Christmas.

Details are a little hazy. I can remember Hugh asking what Mr Yiu what he did back home.

‘Heavy drunkard’ was the answer. What a guy.

So the next day we started cycling again, myself feeling suitably tender and yet to feel the full grip of the impending hangover, which was in the post, and also feeling jealous of Flo, who was fresh as a daisy, the teetotal bastard! I’ll never learn.

The day matched my mood. Drizzle. Until about midday, when the heavens opened and the arse dropped out of the thermometer. It was time for full waterproofs, which did jack shit, as my shoes manage to fill with water whilst riding in the rain, and once your feet are wet, you’re up shit creek.

Some workers waved us over for shelter and warmth inside next to an electrical hazard of a heater. They even gave us some Plov and bread before a bloke wandered in with a snowball in his hand, fortunately from Samarkand, however we weren’t that lucky – as we peered outside the rain had turned to sleet.

The guys wanted us to stay, and the offer was much appreciated, it really was, but the idea of being half shouted at in Russian for the remainder of the day whilst drying off in what was honestly, a shitheap, didn’t really appeal. We decided to wait until the sleet returned to an acceptable level of drizzle and tried to get to Jizzakh, about 30km away and find a cheap hotel to dry out in.

‘I’m flying to India.’ I told Flo. The day had broken my resolve.

‘Have you ever been?’

‘No.’ I knew I wouldn’t even like India, but it’d be warm. The idea of putting up with shit, increasingly cold weather didn’t appeal, and this trip, believe it or not, is supposed to be about fun.

It didn’t change things in the immediate future anyway. The next day we rode in overcast, cold weather, and kipped in a newly built empty house with the permission of the builders working next to it.

At this point I’d almost become obsessed with weather, and fortunately, it was a blinder. We spent the day winding down country roads and small towns before camping at a huge, derelict building. We had no idea what it used to be, but it made a good campsite for the last night of camping in Uzbekistan.

As we checked into a hostel in Tashkent we met Phil.

‘Are you the English and Swedish guys?’

‘One half of it.’

It’s a small cycle touring world. Phil had ridden with Andjali and Camille, the French couple we’d met in Baku. He told me they’d had their tent stolen after they’d stayed at a local’s house. Sometimes bad things happen to good people. They’d offered a spare tent pole for my then knackered tent, and even though the spare didn’t fit, the offer was much appreciated.

Phil was heading a similar way to me, so just as I thought I’d managed to find someone new to ride with, Phil realised his passport had gone missing.

‘Looks like I might be in Tashkent a while longer.’ Phil handled the situation remarkably calmly, yours truly would’ve exhibited a level profanity that’d make Gordon Ramsey stick his fingers in his ears.

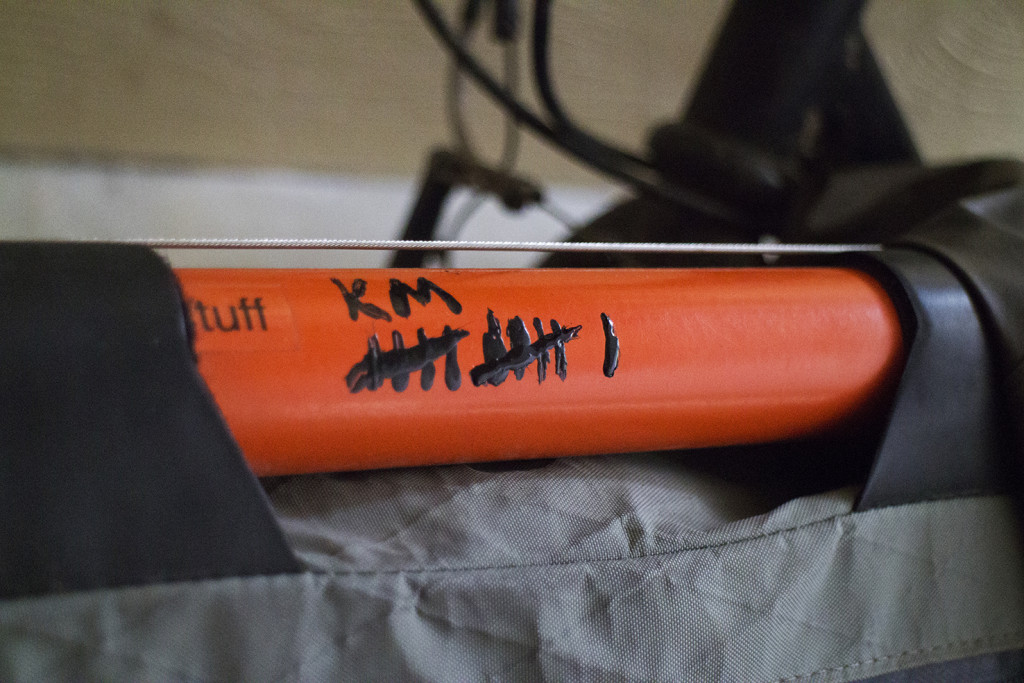

My odometer is shit and can only count up to 999km before returning to zero. I keep a tally on my frame, currently at 11,000km.

So that sealed the deal, after saying goodbye to Flo and Phil, I hit the road. Going solo. The first time since Greece, not a bad run, eh? North to the Kazakh border.

Except it was the wrong crossing, the right one was 30km away.

Bastard.

Flo says:

Hey Sam,

thanks a lot for that account of our few days – and I hope you’re good, where-ever you are right now. and have good weather. I’ll share some pictures with you later.

And thanks heaps for the trip!!!

go with the Flo

December 19, 2015 — 9:58 am

Lizzie says:

Great blog! Not sure if I’m being thick but I can’t seem to find a way of following you on it. Is there one?!

January 8, 2016 — 11:23 am

Sam Pougher says:

Thanks Lizzie! If you scroll to the bottom of the page there should be an ‘Entries RSS’ link, that should let you know when I update, which should be far more regularly!

January 9, 2016 — 1:00 pm

Jayne Drinkell says:

Hi Sam …Happy 2016 . Great read catching up on your journey & photos loving it lots love from Great Grimsby x

January 12, 2016 — 9:38 am

stephen roe says:

“It was at this point I found out when the worst possible moment to get the shits is. There was no avoiding it, if I carried on with tent duty there would’ve been an even bigger problem. If you’ve never had to squat and squirt in a desert plain whilst being pelted by wind and rain, watching your tent try it’s best to roll away, then count yourself lucky.” Sorry I laughed very heartily at this

April 20, 2016 — 11:52 am